Fate Codex

Setting the Stakes

Using variable conditions to set up meaningful conflicts

by June Shores

Have you ever played through a conflict that felt like a slog? Where you weren’t sure what the actual circumstances were? Where the whole thing felt jarring and disconnected? You probably know the feeling in movies, too. The obligatory scene of violence that happens when a producer thinks that the audience is getting bored—the equivalent of the obligatory conflict in a Fate Core session that nobody seems to know what to do with. Both these things suck, and they come from the same sort of place. The game’s GM, like the movie’s producer, wants the game to be exciting so they put things in danger. However, what often happens is that the group becomes confused and goes through the motions, without quite knowing why they’re fighting in the first place.

This isn’t a unique problem to Fate Core, but Fate has special tools that can help the issue. Conditions (page 18 in the Fate System Toolkit) can be used to keep play focused on conflicts, contests, and challenges that matter. By defining conditions in play—during scenes of exposition and other times where things aren’t blowing up—you can lend conflicts, contests, and challenges the weight and clarity that they deserve.

Initial Preparation

To use conditions to keep play focused on meaningful conflicts, start off by using the guidelines from the Fate System Toolkit to create a set of condition slots and include them on the character sheet. Don’t label them with an aspect, though. Leave them blank for now.

During play, blank conditions cannot be checked off to absorb stress. They’re the untapped potential for the stakes of your narrative. When a player eventually fills in the label on a condition, it acts just like conditions normally do. When the condition is recovered—all stress boxes emptied—the player clears the slot and makes the label blank again. The condition label must be replaced with something new before it can be used again. You’ll find more on filling in condition labels and erasing them through recovery below.

Setting the Stakes in Non-Conflict Scenes

In between big scenes of getting things done and coming to emotional, mental, and physical blows, you’ll have quieter scenes where things get set up and you learn about the characters’ motivations. These scenes don’t have to be long, but they should illustrate something that the characters have to lose. If it’s part of a character or campaign aspect, that’s all the better.

Before setting scenes, you should ask directly about the things that each PC fights for. Then, choose one PC’s answers and frame a scene around them, focusing on the elements and characters they draw attention to. Throughout the scene, prod the players to ask themselves “What’s the worst thing that could happen?” That worst-case scenario tells the player what happens when they lose a conflict around the object they care about, and therefore what their condition should be.

After playing the scene to its conclusion, tell players to write in something tangible that could be risked about the object of their care inside one of their blank conditions. The risk shouldn’t be the death or loss of that thing—extremes like that are the result of failing conflicts outright. Rather, the condition ought to be a description of something in the situation around the fictional element getting worse.

Your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man, Peter Parker, has the aspect Caring for Aunt May. His Aunt May can’t pay the bills with her fixed income and she worries about where he goes at night. So, early in the first session his player writes in the sticky lasting condition Losing Aunt May’s Trust. Later, his player decides that he wants to highlight Peter’s misfit nature in high school, so he writes in a fleeting condition, Humiliation.

Suffering Conditions

The process of suffering conditions is more flexible than consequences. From the Fate Systems Toolkit:

You suffer from a condition when the GM says you suffer from a condition—usually as a result of your narrative situation—but you can also use them to soak stress… You can check off as many conditions as you’d like for a single hit.

As a result, players have some more freedom to go to conditions as a cost for a success on a failed overcome an obstacle or create an advantage roll, such as those in a contest or challenge.

Doing so gives contests and challenges more teeth and excitement because there is a risk beyond failure going into them. The player has the choice to have an adjacent situation get worse, or to lose ground in the present situation.

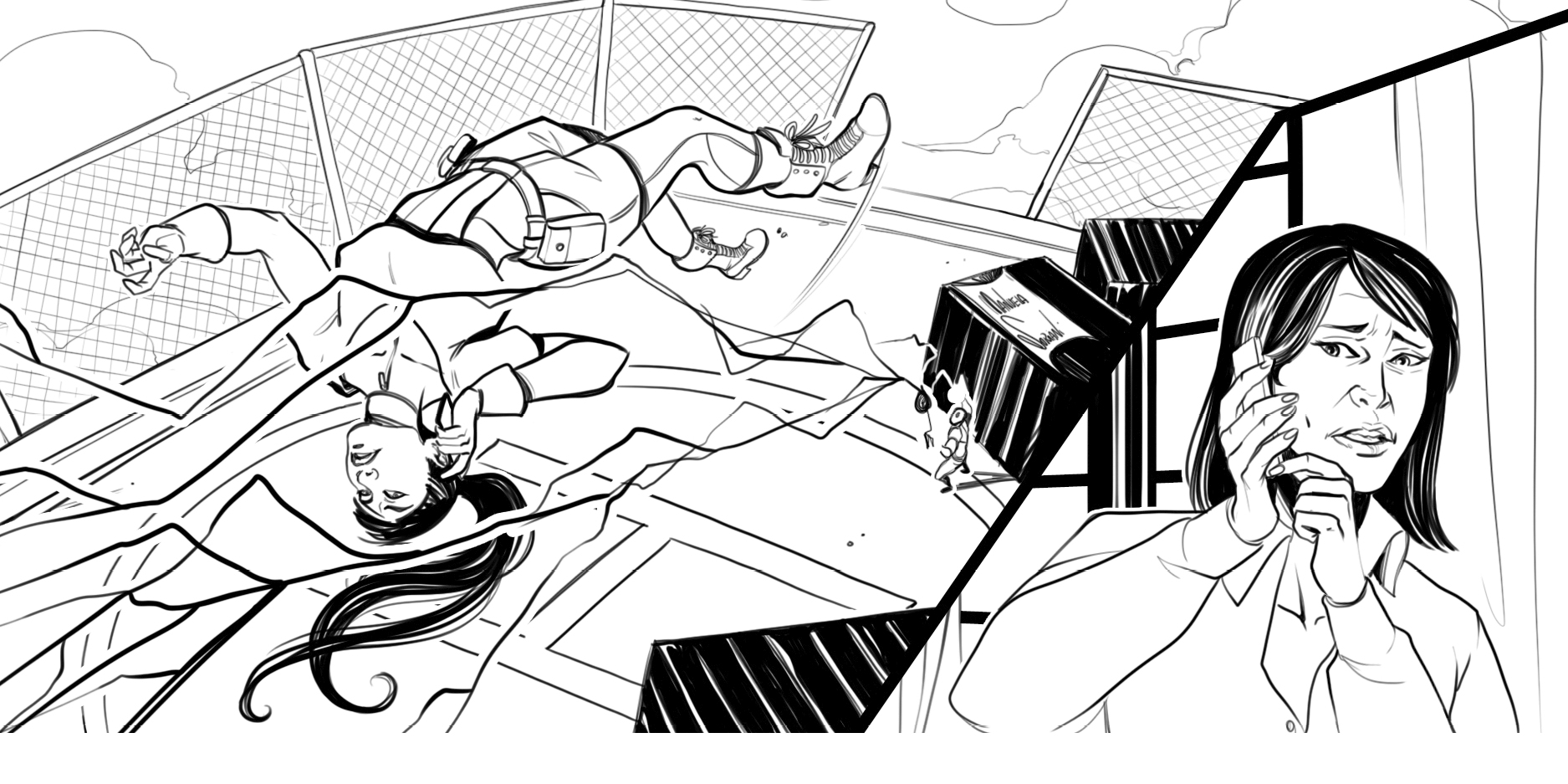

Spider-Man has gotten into a fight with the nefarious Enforcers. To escape them, he has to win a contest. However, he ends up failing a crucial roll and runs out of webbing to swing with. He checks off his Losing Aunt May’s Trust condition and ends up embroiled in the fight. Because he spends so much time in this brawl, he gets home very late. Aunt May is left to worry.

Recovering Conditions

Recovering conditions follows the same process as in the Fate System Toolkit (page 18), with slight adjustments. When a player wants to recover a condition, you should frame a scene around it. Sticky conditions will go away after they’ve been resolved in the fiction. For lasting conditions, once a player has started recovering one, then you should work together to rewrite it and reflect the resolution that comes out of the recovery scene.

Peter Parker comes home late after his battle with the Enforcers and Aunt May is waiting for him. She explains that she worries and that she can’t take him staying out all night. She gives him a curfew and the recovery process for the lasting condition Losing Aunt May’s Trust begins. The aspect is renamed to Curfew and Peter’s player clears the first box, while the second remains checked, as per the standard rules.

Sticky and lasting conditions stick around until fully recovered, checked off and unable to absorb stress. However, compels on them can still be used to complicate the situation. In this case, the condition intrudes on the current situation and raises the stakes of the conflict, contest, or challenge.

While Spider-Man fights Electro, he’s about to create an advantage. However, the GM decides to compel his Curfew condition and have a cross Aunt May call in the middle of the fight. Now he’ll have to talk to Aunt May and fend off her questions while battling Electro.

When a condition is fully recovered, erase it completely. It isn’t an issue anymore and can be replaced with something new.

Rhythm

The flexible conditions system highlights a pattern of natural act breaks in a Fate game. Establishing conditions makes for the first two acts, the exposition and the conceit; the twist comes at the big conflict or challenge when conditions are marked; the spiral comes out of the compels on leftover sticky and lasting conditions; and the resolution comes with recovery scenes.

These pieces come together to make a certain rhythm. You transition between quieter scenes—where you establish the character and their stakes and deal with fallout—and more chaotic scenes—where the situation is changed irrevocably, characters come to blows, and conditions are checked. The pattern helps to reinforce the stakes of the campaign and the arcs of the characters. When they recover their conditions, especially social conditions, they find time for reflection and changing course as they process what happened. When they establish new conditions, they spotlight how their character and the things they care about have changed over time.

Changing conditions, when used to their fullest, can dramatically alter the focus of the game. Instead of the immediate concerns of broken limbs and bruised egos—standard consequences—they instead build in complex, lasting effects that have a real impact on how the story moves forward. Because the players took the time to write them beforehand, when the things that their characters care about are fresh in their minds and they’re not preoccupied with a fight scene, those conditions can carry a lot more narrative weight. They’re also more well defined, so they can be compelled more easily.

Options

This basic system of establishing conditions, spending them, and recovering them can make the context of the characters shine. However, there are plenty of dials to turn regarding the specificity of the conditions and what systems interact with them. Here are a few ways that you can change conditions to work differently in your game.

Stakes Types

The kinds of conditions that you include can inform the tone of your campaign. In a mostly bloodless soap opera, perhaps one involving pastel-colored magical ponies, social and emotional conditions may be the most common. However, in a darker, bloodier game, physical wounds might be more appropriate.

To use this tweak, tell the players what kinds of conditions are fleeting, sticky, and lasting. In a superhero game, you could tell them that a rumor is fleeting, while in a courtly romance game it would be a dire lasting condition.

Mark each slot with a broad category, like “physical” or “reputation.” That way, you guide the players toward the subject matter that you want for conflicts, and the kind of violence—soft, hard, social, etc.—that you want to feature.

Unlocking Stunts

Sometimes you want characters to hold off on using the big guns until some condition is met, like when the circumstances are dire and they have little choice. Sometimes, checking the condition triggers a dangerous power that they can’t quite contain. This is a common trope in shonen martial arts manga and can be tricky to pull off in a game.

To emulate this, attach stunts to certain conditions. Only once a player has marked off the condition, or compelled it if it’s already marked, does the player have access to the stunt. The stunt is then available for the rest of the scene afterward. This requirement creates a bottleneck that keeps a powerful character from steamrolling the opposition by attaching a cost to their power.

Minor Milestones Through Recovery

Minor milestones are often overlooked. One way to highlight each PC’s changing nature, and to highlight minor milestones as a valid option, is to tie them into recovery instead of the break between sessions. Whenever a PC recovers a condition they get a minor milestone and all the perks that come from that. By presenting this as a more interactive part of the game, you make minor milestones more attractive.

Wrapping Up

The context of a conflict is important. Without that context of the character’s status quo and the things they care about, the conflict will flail like a wet noodle. Using flexible conditions will help to make conflicts, contests, and challenges relevant and tense by default. The changing conditions highlight the context of the character’s decisions, bringing the stakes—whether they be social, emotional, physical, or mental—to the fore. It also makes conflicts work faster and hit harder, because you don’t have to think about wording or an appropriate cost in the middle of a scene. It’s all there before the dice hit the table, freeing you up to do more awesome stuff and think about all the ways the situation could get worse. And the worse the odds, the better a PC looks when they triumph.