Fate Codex

Mythos Aspects

EXPRESSING SOURCE MATERIAL WITH PREGENERATED ASPECTS

by JUNE SHORES

Mythos is a concept in TV production, a catch-all word for things like phrases, formula, and motifs that define the aesthetic of a TV show. Battle cries like “It’s morphin’ time!” and setting elements like The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants are examples of mythos in their particular franchise. You might have heard about a similar concept in the Lovecraft mythos, which encompasses Cthulhu and other Elder Gods.

When you sit down to play, say a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles campaign, each player comes with different experiences of the mythos that will inform how they approach the setting. An old-timer who only ever saw the children’s cartoon show when they were small is going to bring very different ideas from the twenty-four-year-old who grew up on the movies and recently did a marathon read of the original, grim-‘n’-gritty Mirage comic books. These approaches can clash and create dissonance and even arguments at the table about what is appropriate for a campaign. This problem can be overcome with a thorough game-creation session, but running one often takes a long time. Working through things together is great! It’s often necessary for players to take some time to hash out what a Fate game is going to look like. But sometimes you want to get everybody on the same page about the aesthetics of a game without taking up a session or more. Sometimes, you want to eliminate blank-page paralysis and get things moving.

In this piece, I’ll show you how to use mythos to your advantage, giving your players solid ground on which to build their characters and letting them know what to expect from the world, by doing these things:

- Writing up a handful of setting and character aspects beforehand will help the players focus on the content the game should include.

- Giving these aspects specific details will make them more concrete in the players' heads, encouraging them to get to scenes faster.

- Asking the players pointed questions about these details will include them intheprocesswithoutsacrificingmomentum.

Making these aspects part of character and game creation can help you to connect the players to the mythos in a big way without needing to take hours to get on the same page. The sort of content that you include in these details and questions will communicate the tone and focus of the campaign.

SETTING ASPECTS

Look at your premise and your genre. What do they look like? What are the iconic, recurring images that come to mind? If you’re trying to emulate something, like Star Wars or X-Men, revisit the source material and examine what makes it feel authentic. What are the big ideas and aesthetic stylings that make it feel like that galaxy far, far away? What works to bring the setting to life, and how can you use that in your campaign? Write these details down. Look for common themes and group them together.

Creating Setting Aspects

Once you have some ideas for the aesthetic underpinnings of your game, you’ll want to turn them into aspects. Some themes are obvious and iconic—the X-Men’s struggle against prejudice, for example, is often expressed by A World That Hates and Fears Them. Other themes are much smaller or rely on other themes to communicate their whole meaning—Star Wars aliens, worlds, and space ships are all wonderfully diverse, and though they might logically be different things, they all make the world feel like A Galaxy Far, Far Away.

Take the details that you grouped into these themes and make a judgment call. What are the biggest ideas that come from the details you gathered? What details can you use to communicate the feeling that you want to lend to your campaign? For each aspect, narrow down the details to a list of four to six. The details that you eliminated are handy to keep in your notes. They are still bundled with the aspects in play and can be brought out when appropriate.

Some of these details are best presented simply. If you want something to be definitely true in your game, make it a detail like “Rodians are bugeyed, twitchy weirdos” or “lightsabers are, in fact, laser chainsaws.” You can convey these details in play.

The other option is to pose a question to the players. The question hints at the detail, but leaves the expression open to interpretation. This is best if the detail varies depending on the context, or if you want to let a player have authority over the detail.

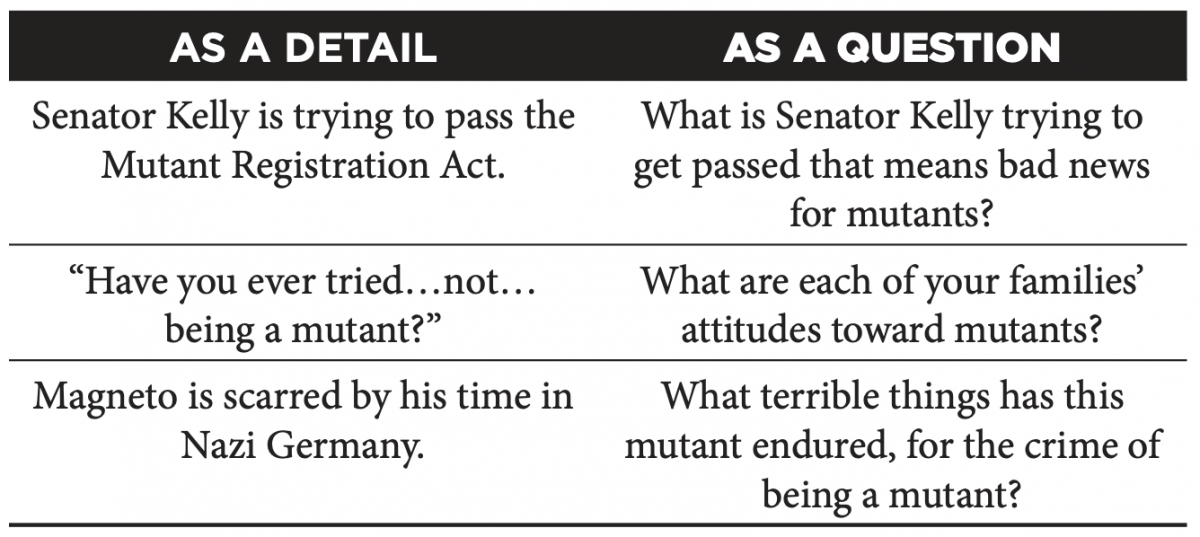

For example, we can take the aspect A World That Hates and Fears Them and narrow down the details like so.

Some of these are better off as details given to the players, others as questions that the players can answer on their own. Some questions might even be asked several times during a single campaign, each answer adding something new to the story. Mixing and matching details and questions is encouraged, since these details will often vary in how specific they’ll need to be and in how much direct control you’ll want over them.

CHARACTER ASPECTS

In addition to mythos setting aspects, you can also create aspects for the characters themselves. When you create player character aspects with mythos details, you’re saying very directly, “These are the kinds of characters that are appropriate for this campaign.” It’s best to keep these aspects somewhat broad, though a couple very specific ones could help push concepts that need more specificity.

The distinction between character and setting aspects is that setting aspects are generally “zoomed out.” A good setting aspect suggests plenty of details or questions. However, most character aspects are already small enough to be their own detail. Instead of making a list of details and questions, let your character aspects be details themselves, and then attach a question to each. This gives you specificity, but still gives each player authorship over their character.

Creating Character Aspects

This process is much the same as creating setting aspects. Look for the iconic character traits and relationships in whatever genre or setting you’re emulating. Keep them broad and look for patterns. Is the leader always in red? Is the rebel always a hothead, or does he feel like he needs to try harder? What difficulties does the brainy inventor have to overcome? What catches your eye about the character and what do they struggle with?

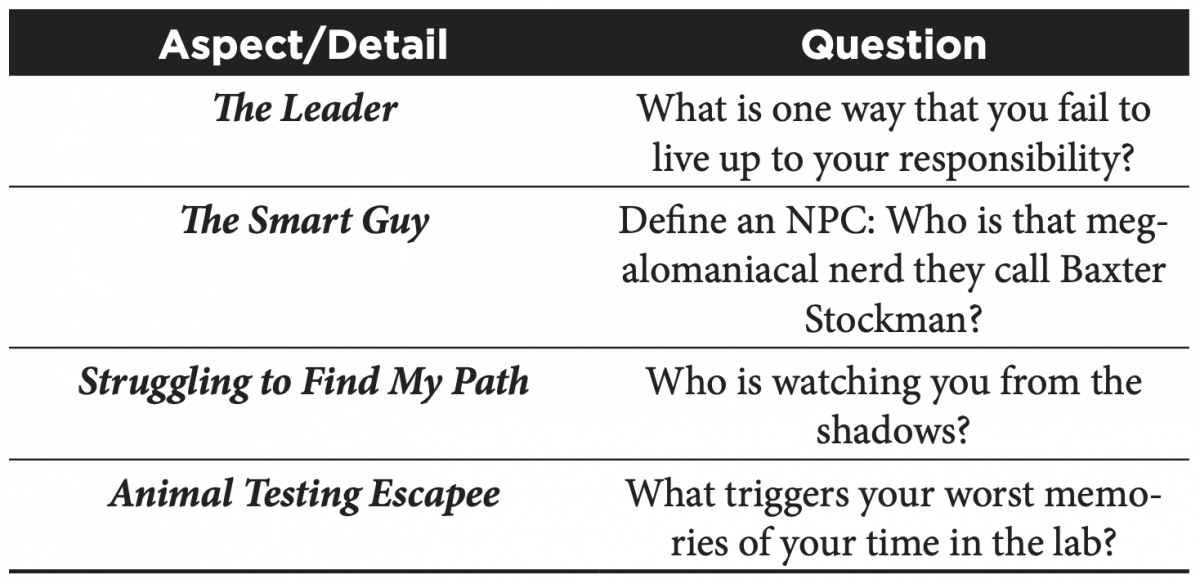

Make each of these details into an aspect, and write in a question to go along with it. Each question should be a counterpoint or embellishment of its aspect, something that could inspire scenes down the road, but easy enough for players to answer at the start of play. They can even be a prompt for a player to describe an NPC’s background. Here are a few examples.

You’ll want to point the players toward a functional group dynamic that echoes your source material, but let the players fill in the blanks with their own details. Encourage them to use their minor milestones to swap out aspects, whittling down their character concept from the broad, archetypal pieces you gave them into a unique individual. During the first few sessions, it’s totally okay for a player to change their high concept into something more specific once they know their character.

The dial to turn here is how many aspects you want to be filled by mythos aspects. For a game that starts with characters in fairly rigid roles, you might have your players choose entirely from lists of mythos aspects. However, more-flexible party makeups might have just three or even two of each character’s aspects slots filled with mythos aspects.

ORGANIZING MYTHOS ASPECTS

There are plenty of ways to organize your mythos aspects in a way that your players can digest. And you’ll want to organize them, because there are few things worse than handing a player a huge stack of cards and asking them to pick five. Option paralysis sets in quick!

Label Organization

If you have a large set of setting aspects, it’s often best to pick and choose them beforehand. But if you have two or three, then just present all of them to the players when you start the game. If you want players to have a hand in choosing these aspects, or if you have a large list, then it might help to label the aspects to help tell the players what’s what. Keep these labels broad; you don’t want too many. Here are some examples.

THEME

A World That Hates and Fears Them

- Senator Kelly is trying to pass the Mutant Registration Act.

- A culture of mutant paranoia

- What terrible things has this mutant endured, for the crime of being a mutant?

Welcome to Mutant High

- Do the students love or loathe this teacher?

- Cold opening in the Danger Room

- Mutations are diverse, but most are useless or strangely specific

Globetrotting Mutant Defenders

- Somewhere new eachepisode

- Mutants endangered, or endangering others

ORGANIZATION

The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants

- Led by Magneto, the Master of Magnetism, Holocaust Survivor

- Mutant supremacists with a mutant populist face

- Gathering forces

Department K

- Turning mutants into weapons (Weapon X)

- “We need a favor.”

The X-Men

- “To me, my X-Men!”

- In Training

- Liaisons to the homo sapiens species

And you might go on to define aspects under location and history labels too, but whatever labels makes sense to you will work.

Character aspects are a little more straightforward: Just take your aspect categories—high concept, trouble, relationship, and backstory in Fate Core—and use those as organizational labels. This makes picking and choosing easy, since you can just slot the aspects in where the character creation rules tell you.

Archetype Organization

Another option for character aspects is to define several archetypes for players to fill. When you note down character aspects from your source material for your players, a rough archetype will take shape for each character. The gist of this archetype will be the high concept. Sometimes you want to keep all of the aspects together in a single pool for players to pick a la carte, which can lead to some interesting character twists. However, for one-shot games or games with fairly rigid canons—say, a limited cast of protagonists that gets recycled in each iteration—more direction might be preferred.

This is just a matter of keeping each source material character’s details separate from the other characters’ and combining characters with similar high concepts. Underneath each character the same organizational labels above apply. Each player chooses a different high concept, and their choices of other aspects are narrowed down to only the aspects under their archetype. Here are some examples.

High Concept: The Rebel

Trouble

- I need to go blow off some steam? (Who has a problem with your reckless streak?)

- Berserker Trigger (What sets you off?)

Backstory

- The Long-lost Sibling (Who is the most important person you met while you were lost?)

- Animal Testing Escapee (What triggers your worst memories of your time in the lab?)

- No Patience (What is your first instinct when you’re made to wait?)

Relationship

- Bullying [Person] Is My Pass-Time (Where does your bullying stop?)

- [Person] Needs to Get Off My Case Already (What does this person criticize about you?)

- [Person] has my back. (What experience brought you and this person closer?)

These lists with preprogrammed choices can almost act like playbooks from Apocalypse World or other Powered by the Apocalypse games, getting the players into the game quickly without handing them a fully pregenerated character.

Going Forward

Using mythos to define the background of your setting and characters beforehand can be helpful in one-shot games where time is at a premium. Long-term games can also benefit from mythos by bringing disparate expectations together or by giving players clear archetypes to build characters from so they can get into play quickly. When setting creation and the phase trio can take a long time, it helps to have something ready to go and inspire your players when a blank page can be exhausting just to look at.