Fate Codex

Cooking Up a Fate One-Shot

by Marissa Kelly

Many of us find ourselves with little free time to dedicate to gaming, and one-shots are the only thing keeping our story-world spinning. Whether at a convention, playing with friends from out of town, or introducing someone new to roleplaying games, we’ve all tried to fit an entire game into one session. In this article, I share my recipe for making Fate fit into one session that efficiently lets you tell an amazing story.

Be Prepared!

You’re only gonna do this once, so you’re gonna want to do it right!

What every Fate game needs to run:

- Three to five people; one will be the Game Master (GM) and the others will be players.

- Index cards or sticky notes.

- Tokens to use as fate points.

Special ingredients you need for a kick-ass Fate one-shot:

- The Deck of Fate, an alternative to using fate dice. This deck of cards mimics the probability of fate dice.

- The X-card, by John Stavropoulos. Available at http://tinyurl.com/x-card-rpg.

Optional:

- One character sheet per player. Downloadable at www.evilhat.com. You don’t need to worry about printing out character sheets for a one-shot—you can just go through each step of character creation together and make sure each player has an index card to write down their character info on.

- List of skills. I recommend using approaches, but if you want to use skills, have a prewritten list of skills that you can place in the middle of the table for players to look at when making their characters.

- Fate Core System, Fate Accelerated Edition, or Fate System Toolkit. If you’re familiar with Fate, you don’t need the rulebooks. In case you want a refresher, there are page references throughout this article.

Setting Creation

Brainstorming can be an adventure all its own, so stay on track.

As the GM, you can help keep the game focused by coming prepared with one or two setting ideas that you would like to run. Presenting options for your group to choose from makes the decision process move along faster. You don’t need to prep a lot, just have a short pitch to give to the group. “Terminator underwater” or “high fantasy in space” are elaborate enough pitches. Familiar pop culture references express the tone of the game quickly and concisely.

After the group chooses a pitch, ask the players questions to create a current issue and an impending issue for the world. It may seem like you’re delaying the adventure by coming up with current and impending issues, but it’s important to set expectations. If everyone has a sense of the story’s direction before play starts, they can help each other get there. Using your limited time to set up issues creates a high level of buy-in for you and your players. When everyone has a chance to contribute something, the story is more compelling for the players because everyone helped add depth and history to the setting.

Player-generated issues also take the weight of coming up with plot off the GM’s shoulders. During setting creation, the players tell you what issues they want to engage in. Listen to them and be prepared to run with it once the game starts.

Asking the players to tell you what issues they are interested in means that you don’t have to guess what kind of themes and challenges they want to encounter, but it also means their answers may surprise you. When they come up with something that you weren’t expecting, set a scene that explores what you find interesting about it. You only have a few hours to play, so it’s important that you’re excited about running each and every scenario.

The Questions

To make sure everyone gets a chance to contribute to the setting, go around the table and ask one player at a time to answer a question about the setting. By asking the question to only one player at a time, decisions can be made quickly. Also, this ensures that all of the players have a chance to contribute to the setting and be heard. Remember, the more invested they are, the better time everyone will have.

What Is the Current Issue?

Limit your table to one current issue for your game. Although two current issues would increase how vibrant the world is, in one session there isn’t enough time for the characters to interact with more than one.

Start by passing the spotlight to one of the players at your table and ask them directly, “What longstanding problem do the people in the setting face?” (See: Fate Core System, page 22.)

What Is the Impending Issue?

Once you have your current issue, pass the spotlight to the next player at the table and ask them, “What facet of the current issue threatens to ruin the setting if nothing is done soon?”

If necessary, rephrase the impending issue so it’s an immediate enough threat that the players can engage it when roleplay starts. You will constantly refer back to this part of the fiction and use it to construct what’s at stake for the final conflict. (See: Fate Core System, page 22.)

Who Are the Faces?

Continue to pass the spotlight around the table and define one face for the impending issue and two faces for the current issue. If you limit the number of faces to three, you can ensure that all of the NPCs can enter play if needed. Name each face and give them a (public or private) goal. Faces are tied to either the impending or current issue, but they should also have a clear motivation and/or drive to continue being part of the story. Each NPC is a useful tool for signaling to your players that something interesting and important is happening.

Make the face associated with the impending issue an important figure, like someone with power or influence over a faction or corporation. Guide your players by asking, “What powerful person has a stake in how the impending issue is resolved?” Use the presence of the face of the impending issue in a scene to signal to the players that they’ve impacted the world in some way. Make it explicit through the NPC’s dialogue, even if it’s just a message over a PA system during the epilogue of your session.

Make sure the two faces associated with the current issue are opposing forces. Ask your players, “Who benefits from the current issue?” and “Who is trying to change the current issue?” If you have a mega-corp that’s taking over the world, two opposing faces might be a corporate bigwig and someone working to take down the mega-corp. Showing an active conflict guides the players’ actions and makes them feel like they can jump right in to the action by taking sides. Instant drama!

If a player is having trouble creating a face, ask guiding questions like “How do this face’s goals oppose the other faces?” or “How does the face’s goal drive the face to remain engaged in the world?” Asking questions helps the player flesh out what they really want out of the story, rather than imposing your own solutions. (See: Fate Core System, page 26.)

What Are the Places?

Now it’s your turn, as the GM, to put a name to some places that have come up during setting creation. Name two places that you want the players to be drawn to. Your adventure will take place in these two locations, so make them interesting and different from each other.

Naming the two locations gives your players a heads-up about where their adventure will take them. If your places are a warehouse and a fancy penthouse, starting the adventure in the penthouse means that every player knows that the warehouse is where it will all go down later. You can create faces for these locations if you need more ways to draw the players in. (See: Fate Core System, page 26.)

Character Creation

Grab your pencils, the heroes have arrived.

Fate is an open-ended system that allows you to create any setting you want, but that open-endedness can also lead to time lost at the table during character creation. Asking your players a specific question for each aspect reduces the chances of choice-paralysis.

Aspects

Ask the following questions (one at a time) to the whole table. Give them time to think about and write down their answers. (See: Fate Accelerated Edition, page 30.)

High Concept: Easily illustrated as a motto, quirk, or personality trait.

Question: When danger strikes, why do people call on you?

Trouble: Easily illustrated by a weakness, enemy, or obligation the character has.

Question: Why do you have difficulty getting close to people?

Go around the table and have everyone introduce their characters!

Next, have the PCs each think of one more aspect: their relationship aspect. To define the relationship aspect, have the players answer the question below about a relationship they have with the PC to their left. This aspect establishes existing history between characters as well as fleshing out a third aspect they can use during play.

Relationship: Easily illustrated as an obligation, motto, or weakness.

Question: What did your character do for them or say to them in a time of need?

Approaches

Use approaches instead of skills to keep the ball rolling for a one-shot game. Approaches help players describe their characters quickly as well as signal to the entire party when they may be “breaking character type” to take a radical or heroic action. (See: Fate Accelerated Edition, page 12.)

Stunts

Stunts let a character “break the rules” in a way that fits their character concept. Rather than spending time with each player to come up with cool situational powers that they might use during the game, wait for opportunities during play. When a player describes something badass that they want to do—and their character concept suggests that they should have little to no trouble accomplishing it—write a stunt for them on the spot.

When you create a stunt on the fly, ask yourself if this is something the PC should be doing a lot or if it’s too powerful to be used more than once. If it’s recurring, write a stunt that allows for a situational +2 to an approach or a skill. If it’s a “Hail Mary” kind of stunt, make it something they can use once this session or at the cost of a fate point. (See: Fate Accelerated Edition, page 31.)

Stress

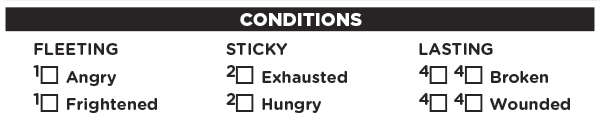

Stress can sometimes seem like recordkeeping that takes you out of the fiction. To keep your one-shot spicy, use conditions rather than a stress track and consequences. This keeps the damage descriptive and creates a feeling of immediacy when your players take damage or stress. When a PC takes a hit, they can mark off one or more conditions. A fleeting condition absorbs up to 1 stress. A sticky condition absorbs up to 2 stress. A lasting condition absorbs up to 4 stress. Mark all the boxes for a condition when it’s taken. The character now has that condition’s aspect, and opponents have a free invoke they can use to take advantage of your condition’s aspect. The aspect lasts until you clear the condition.

From Fate System Toolkit, page 18

“There are three kinds of conditions: fleeting, sticky, and lasting. A fleeting condition goes away when you get a chance to catch your breath and calm down. A sticky condition stays checked off until a specific event happens. If you’re Hungry, you’re Hungry until you get a good meal. Wounded and Broken are both lasting conditions. These stick around for at least one whole session, and require someone to overcome an obstacle with a passive opposition of at least Great (+4) before you can start to recover from them. Lasting conditions have two check boxes next to them, and you check them both off when you take the condition. When recovery begins, erase one check box. Erase the second one (and recover from it fully) after one more full session. You can take a lasting condition only if both of its check boxes are empty.”

To keep things simple, ask every player to choose between two boxes of Broken or two boxes of Wounded. Asking your players to choose which conditions they want (mental or physical) allows players to further define their characters. (See: Fate System Toolkit, page 18.)

Fate Points

Great news about one-shots is that you don’t worry about refresh! Everyone just starts with 3 fate points. Done and done.

Playing the Game

Time to jump into the thick of things. It’s not over till it’s over!

Time is always a pressure, and deciding where and how to spend it is key. This section contains in-game tools that aid in creating a satisfying one-shot game in Fate.

The Deck of Fate

Use the Deck of Fate to help you save even more time by eliminating excessive dice-shaking and math. When using the Deck of Fate, shuffle after every +4 or -4 is drawn. This ensures that no one is safe from those results going forward. Fate dice or other generators can be used in a pinch, but the deck is the fastest way to get results.

Strapped for Resources?

The Deck of Fate can also double as fate points—just don’t forget to shuffle them in with everything else when you hit a +4 or -4.

X-card

Available at http://tinyurl.com/x-card-rpg

“It’s a card with an X on it that participants in a Simulation or Role-Playing Game can use to edit out anything that makes them uncomfortable with no explanations needed. It was originally developed to make gaming with strangers fun, inclusive, and safe.”

The X-card allows everyone to be on the same page throughout the game. If someone isn’t having fun, then you should be able to quickly correct it and move on with the story.

Challenges, Contests, and Conflicts

Because you have one shot to squeeze an epic plot out of this game, only focus on two encounters. The first is a quest or mission that can be easily resolved and sets the stage for the second encounter. Make the second a world-changing event or showdown that demands action from the PCs.

Introduce threats to your group using challenges, contests, and conflicts, depending on how much time you want it to take. Challenges generally don’t take a lot of time and are best used when setting up a bigger conflict. Contests can happen at any point in the story and usually focus on conflict between PCs. Conflicts take a lot of time and energy, so only introduce one and save it for last.

Base the first encounter you present to the players around a challenge that uses the current issue and one of its faces. Make the first encounter a challenge—not a contest or a conflict—and set it at one of the defined places. There’s no need to plot out how it should resolve (negatively or positively) because the major conflict hasn’t played out yet. Whether your heroes go into the final act feeling prepared or just having taken a loss, they can still have a satisfying end scene.

Make transition scenes short and use NPC interactions, like threats or praise, as well as describing changes in the environment that PCs may have caused, like heightened security or a sympathetic underground movement that’s ready to assist the PCs in their cause.

The second encounter is the final conflict. Use the remaining place you created at the beginning of the game and incorporate the impending issue and its face into a conflict for the PCs to overcome. Revisit what the impending issue is and what goal its face has, then make the conflict explicit by spelling out what the players are being asked (by an NPC faction) to do and how their involvement can impact the impending issue.

Because the impending issue was created as a looming threat to the setting, the PCs will feel like they have a chance to impact the world by eliminating, failing, or perpetuating the problem at stake. Be prepared to follow through on that promise, even if you run out of time—use the epilogue to show them that their actions had an impact. (See: Fate Core System, page 146.)

Epilogue

If you sense yourself running out of time to finish your final encounter, look for a stopping point. A good stopping point is any time a PC has just accomplished or failed an action. If your party is split or executing multiple plans at once, look to wrap up an action with each of them individually. Once it’s clear that all PCs’ actions have resulted in a failure or success, it’s time for the GM to begin epilogues.

With the goal of tying up some loose ends in the scene, describe what impact the PCs’ actions had on their immediate surroundings. What do the “bad guys” do? Do they escape, see the error of their ways, get disposed of by restless citizens, or get betrayed by someone close to them? Also describe what kind of physical impact the PCs may have had on the landscape. Does the sun begin to rise, symbolizing a new beginning? Do the PCs have to wait for the dust to settle over the rubble to see if their friend made it out? Tell the PCs what they lost and what was saved because of their actions. Whatever you choose to describe, refrain from telling the PCs what their characters do or do not do; they’ll have a chance to explain what they got out of the encounter once you’re done.

Even after the GM finishes up the final scene, the end of your encounter can feel like a cliffhanger, so go around the table and give each of the players the spotlight to share a short summary of what their character does in the world following the conflict. This can describe immediate actions, like chasing down an NPC in the pursuit of justice, or future actions, such as retiring from a life of violence and wandering the world till the end of days. If the scene they describe involves another PC, have them ask for that player’s permission. The one-shot ends with a satisfying montage of character stories for your group as the PCs tie up loose ends that they found important.

Roses and Thorns

“Roses and thorns” is an out-of-character way to get feedback and make sure every person has a chance to voice concerns and praise. This generally happens naturally after a game, but the structure makes sure nothing and no one voice gets left out.

Go around the table and ask each person (including yourself) to share one thing they liked/thought worked well during the session (the rose) and one thing they didn’t like (the thorn).

Fin!

GMs, designers, and players all have different schedules, but no matter how much time we have to dedicate to it, collaborative storytelling should be a fun and fulfilling experience. I hope this recipe helps you cook up even more Fate games with the limited time you have!