Fate Codex

Rethinking Stealth

by koji nishiuchi

Stealth comes up a lot in just about every kind of adventure. Whether it’s a costumed vigilante lurking in the rafters before a flashy entrance or a terrified teen hiding in the closet from the supernatural serial killer, there are times when the question “Can they see me or not?” becomes vitally important. Stealth is common in RPGs, too—just about every system with a list of skills has at least one focused on stealth.

The Problems of Stealth

In roleplaying games, stealth almost always works the same way: you roll how well you can hide against how well your opposition can spot you, and if you fail, you’re found. It’s a simple rule, and at first glance it seems to intuitively capture how hiding works in fiction. The problem is what happens when you put those rules into practice.

Pass or Fail?

The first time you fail a Stealth roll, you’ve failed the whole stealth mission. That’s because once you’re spotted, it’s no longer a stealth mission. It’s either back to combat as you fight your way through, or a chase scene as you run away. Since you generally only use stealth when it’s needed—to avoid a lethal encounter or big social consequences—this failure can range from disastrous to deadly.

Because the consequences of failure are so drastic, if you want to use stealth, you need a high Stealth rank. While it’s perfectly acceptable to go into combat with a 50% chance of hitting and a 50% chance of being hit, attempting a Stealth roll with just a 50% chance of success is crazy. It gets even worse when you’re called upon to make multiple rolls at multiple checkpoints against multiple guards while sneaking. Because it only takes one failure to ruin everything, using stealth is heavily punished if you can’t reliably—almost trivially—succeed at all times. Even if your character has Great (+4) Stealth and is only up against guards with Fair (+2) Notice, by the third roll you’ll have an 88% chance of failing without dipping into your precious reserve of fate points.

But what if your character has a stunt gives them a reliable +2 bonus to their check? What if it’s +6 against the measly +2? Then you run into another problem: If you can succeed every time, there’s no tension or challenge. If you can’t succeed almost every time, trying to sneak around is likely to cause more trouble than it’s worth. While that all-or-nothing approach might work for some, there should be a middle ground.

Solo Stealth

Beyond the all-or-nothing nature of stealth, there’s another fundamental problem: because stealth is the domain of the expert, non-experts get left behind. When the thief scouts ahead, they get cut off from the party, and if they do get spotted, they’re in a whole bunch of trouble. Meanwhile, the other PCs need to…wait—possibly for a whole session. Alternatively, a GM might actively discourage stealth, whether by shaping the adventure to not need stealth, or by making the risks too high, the rewards too low, or the odds too stacked against the stealth expert’s favor, punishing them for their investment in the skill.

Now, it could very well be that a GM wants to punish stealth. Maybe stealth doesn’t fit the kind of game they’re interested in running. Maybe they’re more a fan of big action pieces or social drama, where stealth is out of place because it’s much quieter and solitary by nature.

This is a false choice, though. Giving power and utility to stealth need not also make it time-consuming and unbalanced. So when a GM wants to allow a player to be stealthy, but at the same time they don’t want that player to hog the spotlight, they have options.

Making Stealth Work

These problems aren’t new. They’ve been around from the beginning of tabletop RPGs, appearing in system after system, accepted as just the way things go because most RPGs don’t have the tools to tackle the problem at its core. In such games, by trying to emulate reality, it’s a challenge to represent stealth in a satisfying way. Simulating stealth can be an even greater challenge than simulating combat, though. You have to consider lines of sight, the ambient lighting, the abilities and skills of every single NPC in your path, and more.

Fate isn’t like other RPGs, though—it does have the tools to make stealth worthwhile. Since Fate is all about emulating fiction, not reality, we can think about how stealth fits into stories.

In fiction, stealth tends to be used in two distinct ways. At one end of the spectrum, there is slinking through the shadows, climbing among the rafters, and slowly slipping past detection. At the other, you have dodging just out of someone’s field of vision, throwing down a smoke bomb to hide in the fog, jumping out of the shadows and retreating back in, or taking the chance to run for your life. We’ll call these, respectively, Sneaking and Hiding. These aren’t new skills, but they will let you use the Stealth skill in new ways.

Sneaking

Actions in Fate can be split into two categories: quick actions and long actions. Quick actions are things like attacking a monster, jumping a chasm, or noticing a trap. They happen more or less in real time. Long actions are things like researching an ancient cult, finding a buyer for a highly illegal magical artifact, or combing a crime scene for clues. They can take minutes, hours, or even days to complete. Often, players will focus on the quick. They’ll say they want to do something, roll the dice, and then it’s done. Longer things are thought to be more boring, the kind of “downtime” events that go on between adventures, like crafting magical items or learning new languages.

Stealth is generally a quick action. You hide and move silently while hoping not to be seen. But you can also use stealth as a long action—Sneaking. Like other long actions, Sneaking can take minutes or hours to complete, as your character carefully studies the environment, analyzes patterns, and only moves at the absolute safest moments. In exchange for taking up extra time from the character’s perspective, Sneaking is generally safer and, perhaps paradoxically, much faster for the players than standard Stealth. That’s because while the normal Stealth approach has you go through every obstacle and encounter on its own, the Sneaking approach can boil it all down to a single check.

When you make a normal Stealth roll as a quick action, it’s opposed by the Notice ranks of any would-be observers. With Sneaking, you roll only once against a passive difficulty. Say a player wants to scout an orc war camp. If you run the conflict like a typical roleplaying game, the player might need to succeed on many overcome rolls to slip past multiple sentries, succeed on some more against lower difficulty to get past off-duty warriors, and do it all over again on the way out. A single failed roll will lead to them being surrounded and outmatched in a deadly situation. Though from the character’s perspective they might be done in just a few minutes, it could take upwards of an hour for the player and GM to run this solo mini-session.

A Sneaking roll condenses all this into a single create an advantage roll, with success revealing useful aspects about the war camp. Failure would mean the character can’t find a way to sneak into the camp, but wouldn’t alert the camp to their presence; success at a major cost could be the very opposite, getting them the info, but just as they’re slipping away a twist of fate has them spotted and then chased all the way back to the party. From the character’s perspective, the act of Sneaking could take three hours or more, but from the player’s perspective, it’s a brief conversation with the GM lasting a few minutes at most that moves the fiction along quickly.

Alice is running a typical fantasy adventure game. The party’s ranger sees signs of a band of orcs nearby. Gary is a rogue and wants to scout ahead to see what the party is up against.

Alice: Okay, that sounds like you’re creating an advantage using Stealth. I think the difficulty is only Average (+1). Roll it.

Gary: All right. +3 Stealth, and I rolled ++-0, so that’s a +4!

Since the orcs aren’t making any effort to conceal their tracks, they’re easy to follow and easy to spot. Gary’s tiny halfling can easily avoid the orcs detecting him. Since Gary succeeded with style, he can get a lot closer and get a better look than your average adventurer.

Alice: You follow the tracks to the edge of a campsite where you see a band of a dozen orcs. They seem to be relaxing and drinking, settling in for the night. If you hold the party off for a while, you can take advantage of their Relaxed and Drunk aspect with two free invocations. But don’t take too long because you also see some human captives in some crude wooden cages, and those cooking pots aren’t for veggies. Even though the camp is only a few miles away, you moved slowly to avoid detection, so the whole thing took two hours.

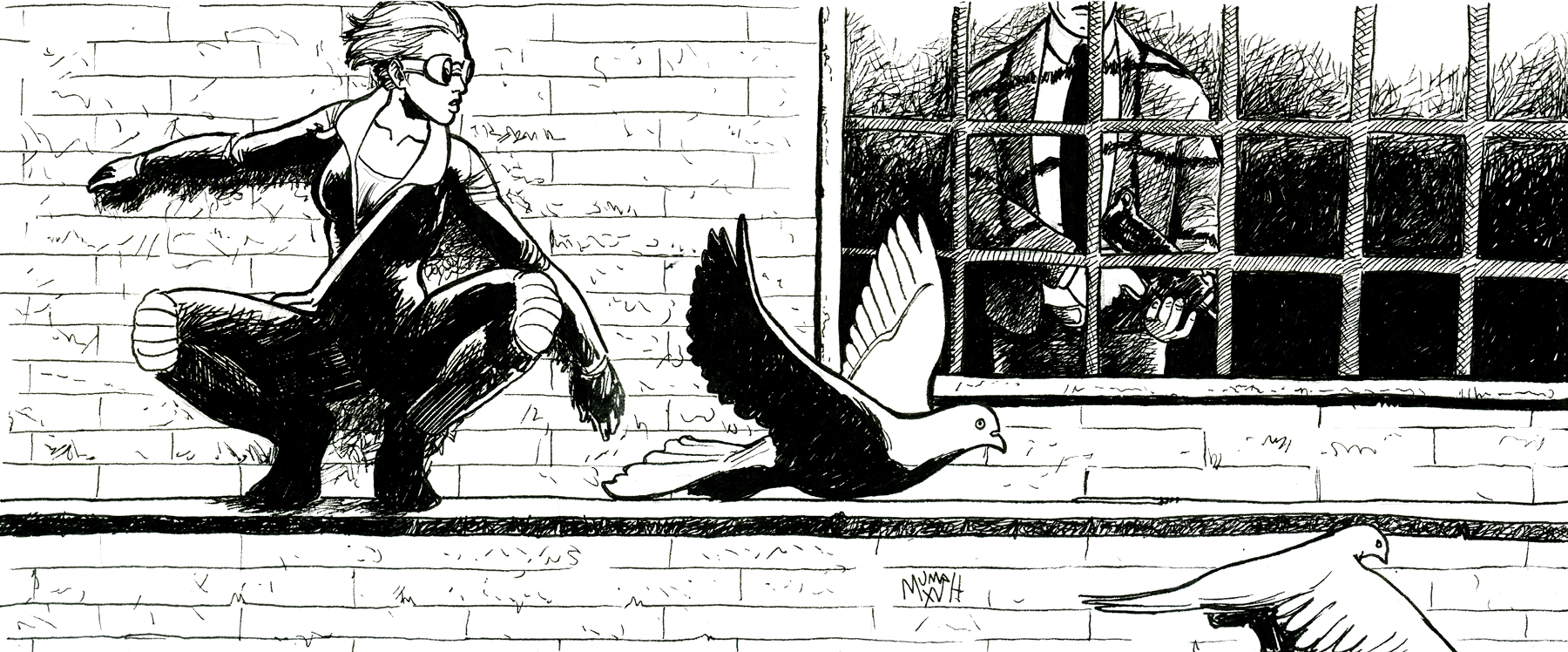

Alice is now running a game of superheroes and villains, and Gary is playing a catsuit thief with ninja training named Ninja Thief. Gary wants to steal the legendary Masamune katana from the superhero headquarters of the Super Seven.

Gary: Okay, so I know it’s in Samurai Hero’s office, just sitting on his desk. So I head there as stealthily as I can.

Alice: There might not be a building in the whole city with tighter security, not to mention the ever-vigilant superheroes always keeping watch. Just getting that far, you’re going to need to roll at least a +7.

Gary: Okay, well, I have +4 Stealth and my Shadow Ninja stunt gives +2 at night. Rolling...and it’s a +5. I don’t really want to spend any fate points here. I think I’ll take the failure.

Alice: After spending two days staking out the Super Seven Tower, you see no weak points. The security there is just too tight. You’ll need to find a way past or think of some other way to steal the sword.

Gary: Okay. In that case...hmm...I bet it wouldn’t be a problem if I was wearing one of the Steel Sentinel’s extra suits. I think I’ll call up my contact who offered to help me get close to one of the suits last session....

Hiding

If Sneaking is the long-form version of Stealth, Hiding is moment-by-moment evasion. Hiding most often comes up in two situations: when a PC has been spotted and wants to regain their hidden position, and in combat when a PC wants some concealment for just long enough to launch a sneak attack. The biggest difference between Hiding rolls and other kinds of Stealth rolls is that a player only uses Hiding when someone is already aware of their presence and is actively looking for them.

Like Sneaking, Hiding is a create an advantage roll. When you want to hide, roll Stealth against the highest Notice of the opposition. On a success, your character gains a Hidden situation aspect to describe their success at avoiding detection. Like with other situation aspects, you can invoke these Hidden aspects to improve your attack and defense rolls. It can also provide +2 passive opposition to attacks as you make yourself a difficult target. This passive opposition doesn’t stack with a character’s skills for defense rolls, though, so if a player has a higher-ranked defensive skill, such as Athletics or Fight, they’ll want to roll with the skill instead of relying on the passive opposition.

While Hidden, a player can create an advantage, opposed by the opposition’s highest Notice, to place additional free invokes on their Hidden aspect. The player can then offer compels to the GM on that Hidden aspect so that they can safely escape. Persistent pursuers might want to resist the compel, spending one fate point per free invoke on the aspect. This integrates Stealth with the standard rules of conflicts without boiling things down to a single check at one end or forcing players to concede in order to escape at the other.

The Hidden aspect, just like any other situation aspect, is not a blanket permission to ignore all the other characters. An enemy can still attack after they’ve been Blinded or Stunned, and a PC can still be attacked even though they are Hidden. The player can invoke the aspect turn a hit into a miss with the +2 bonus—because, naturally, it’s more difficult to attack someone who is hiding from you—or offer their opposition a compel to get away from danger, but they are otherwise just as vulnerable as anyone else.

You may wonder, doesn’t it make more sense that a Hidden aspect must be overcome before a PC can be attacked? For two reasons, no. First, consider the kind of scene that comes up when someone uses stealth in a fight: weaving in and out of smoke, fog, or shadows for strikes, all while the opponent lashes out constantly, trying desperately to predict where the next attack will come from. Sometimes, with enough battle instinct, they land a blow on their stealthy opponent.

Second, and of even greater importance, is that if the Hidden can generally only be overcome with a single skill (Notice), the balance of the game breaks. Badly. Characters with low Notice would be nearly helpless against even moderately stealthy enemies. And while it might be fun letting someone get away with being invincible, that kind of power can offer perverse incentives, incentives the players might end up pursuing even if it goes against their character concepts or the fun of the game.

Back in the fantasy adventure, the party has launched a surprise attack on the band of orcs. The party’s wizard started things off by conjuring up a Foggy Mist, and Gary used create an advantage to give his rogue the Hidden aspect, before attacking on the second round.

Alice: Okay, round three. The orc chief pulls the knife out of his shoulder, then he’s going to try and kick the halfling that stuck him with it. He gets a +5.

Gary: Okay. Rolling…+4. Wait, how can he even find and attack me if I’m all super hidden in the fog?

Alice: Logically, he can’t. You can use one of your free invokes on that Hidden aspect to turn that hit into a miss.

Gary: That makes sense. I’ll do that.

Alice: The orc swings wildly in the fog. His massive blows create gusts of wind that carve up the fog, but he only strikes empty air while the halfling snickers from a safe distance.

Gary’s plan to steal the extra Steel Sentinel suit on display at the Superheroic Super Museum was a success, but before he could disable it, it sent out an alert. Clearly outmatched, Gary wants to escape ASAP.

Alice: The guards chasing you roll a +6, dealing another four stress. So that’ll be a moderate consequence unless you want to be taken out.

Gary: Conceding would mean I get away, but without the suit, right?

Alice: That’s right.

Gary: Forget that! I’ll take the moderate consequence, then I’m getting out of here. Going to keep running and create an advantage again for my Hidden aspect...and I got a +5. Can I get the guards to lose me if I offer a compel with that aspect?

Alice: The guards get a +2 on their Notice roll, meaning you succeed with style. You had a free invoke on your Hidden aspect already, so you now have three free invokes. Since they only have two fate points, they’ll have to take that compel and you’re in the clear.

Gary: Awesome!

Final Thoughts

Neither Sneaking nor Hiding is a new rule. They’re just two different approaches to using the basic rules of Fate Core. The advice is also very general, suited more for games where stealth is one factor among many rather than the most important element. In a game about thieves or ninjas, it can be fine to zoom in on each stealthy encounter and treat a high Stealth rank as an absolutely broken advantage in combat. And in a game of adventurers, if one player can alter reality on a whim while another can wrestle a handful of demigods at a time, it would be less of a problem for the rogue’s Hidden aspect to make them nigh invincible.

It’s up to a GM to pick the best tools for the job at hand. The goal here is simply to sharpen a few of those tools.

Bonus Stunts

If you do use these guidelines, it can be helpful to have a few stunts on hand for players to customize their approach to stealth with. They’re only examples, though: just like anything else in Fate, you can use them as they are or as inspiration for designing your own.

Quick Scout. +2 to Stealth when used for scouting and reconnaissance, and when you succeed with style on such tasks, you finish in a fifth the normal time it would take.

Careful Scout. +2 to Stealth when used for infiltration and thwarting security attempts. If you fail, you can try again, but the second attempt takes twice as long.

Infiltrator. +2 to Stealth while hiding in plain sight, disguised as an evil henchperson, hapless low-level employee, mindless zombie, or something similar, as long as you aren’t recognized.

Backstabber. Once per session, gain +2 to attack an enemy while you are Hidden.

Absconder. +1 when using Stealth to defend against Notice. Also, if you compel an opponent with your Hidden aspect to allow you to escape, they must spend 2 fate points to resist it.

Getaway Planner. When you compel your Hidden aspect to escape from a conflict, you can take others with you. For each fate point beyond the first added to the compel, whether by you or another party member, you can take someone else. +